We want to show something intimate about the main character, to share a little more about the ideas behind her creation and the different versions she went through until reaching this moment.

Early versions of Espada

In the image above we have two early versions of Espada: on the left, the very first way we imagined her, and on the right, how we considered including her in the first version of the project.

From the beginning, Espada has always had yellow as her main color. This color is important to us—it symbolizes the fight against depression and is inspiring to look at. She has always been accompanied by a weapon, in this case a sword, which represents courage and determination to face struggles. That is why her name, Espada (“Sword”), represents both the challenge and the journey she must endure.

Although the early versions were interesting, the overall idea of the project was different, and the character felt a little out of place within this new approach. Once we finally decided what the game should be and the kind of message we wanted to deliver, we realized the style also needed to change. That led us to the conclusion that a single style wouldn’t be enough—we needed two versions to fully express the concept of the game we were creating.

Since the game involves an artistic experiment with trixel art, our character had to exist in trixel. But on the other hand, we also needed a way to represent her with more detail and to bring out the expression of the girl we created for the adventure. That meant we had no choice: we needed both a trixel version and a digital painting version that could better reflect the idea.

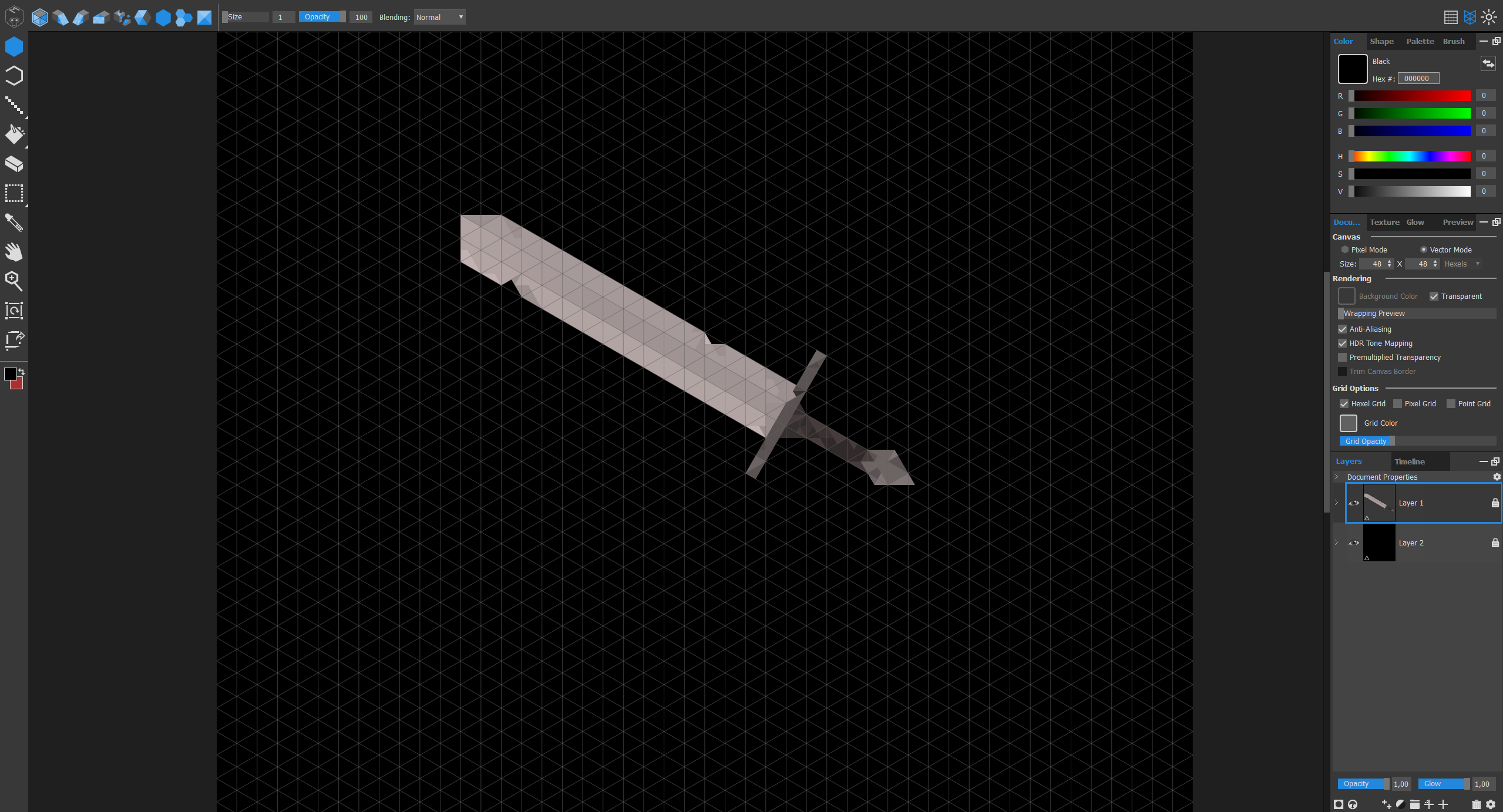

Sketches of Espada in her current version

The image above represents the current digital painting version of Espada. It has far fewer details than the first version we presented before. That way, we could keep her closer to the trixel version, which, due to its limitations, makes it difficult to include many details. Interestingly, this version didn’t go through many drafts—we basically reached it as soon as we understood what the game should be, almost as if the character herself was already explaining how she wanted to exist.

The trixel version below also had an early draft that represented that old version of Espada. But we quickly realized it wouldn’t work. Soon after, with only a few attempts, we managed to make the character much more compelling.

Left: first trixel version. Right: current version.

It’s important to remember that this art form is limited, and for the project, we imagined everything as if it were a board game—a more playful form of expression to deliver to the player.

The image below shows another version of Espada, but this one doesn’t appear in the game. It was made only to inspire us during development.

Mascot version, made in amigurumi.

What matters is not the shape of the character, but what she means to the project and to our lives. Working on this game is not just fun, but also a reminder that it is possible to fight for the things we want. Even if many versions are needed, the most important thing is to keep trying.